Should a Pentecostal Education be a Feminist Education?

Including Female Voices in (Pentecostal) Theological Education

Note: This material is taken from my presentation at the Society for Pentecostal Studies 2025 meeting, where the theme was:

"MORE THAN A SONG”

Scholarship as Worship In the Church, the Academy, and the Public Square

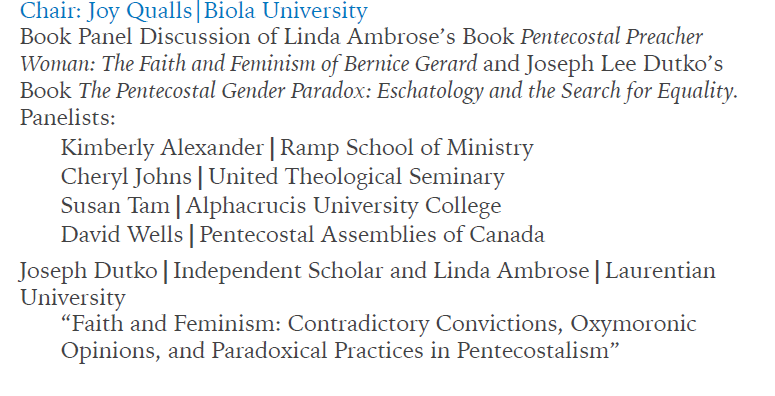

The session was also a book panel discussion on my book and Linda Ambrose's book on Bernice Gerard. Here's the description from the SPS Program:

Much of the material from this presentation is edited content from my book The Pentecostal Gender Paradox: Eschatology and the Search for Equality ©2024 by Joseph Lee Dutko. Used by permission of Bloomsbury Publishing (www.bloomsbury.com).

Except for a few exceptions, footnotes are not included below for easier reading in blog layout. If making any citations or quotations from this material, please refer to the book pages 214-220.

* * * * *

Part of my task for this panel is to simply “set the stage” for our discussion on faith and feminism in Pentecostalism.

So this is a bit of a full circle moment, at least for me.

In February of 2014, I drove several hours roundtrip one evening to Trinity Western University in British Columbia to hear Linda talk about her beginning research on Bernice Gerard.

It was my first time meeting Linda (she probably doesn’t remember meeting me!). But we chatted, and I was inspired by her talk and shared with her my research idea--still very much in its infancy--on the relationship between eschatological beliefs and gender practices.

Well exactly 10 years later, in 2024, both of our books were published, and now here we are together.

Our title (“Faith and Feminism: Contradictory Convictions, Oxymoronic Opinions, and Paradoxical Practices in Pentecostalism”) combines a lot of the key themes, even phrases, from Linda’s work and my work, which in different ways seek to resolve or reconcile the paradoxical relationship or impulses between conservative religion such as classical Pentecostalism and feminism.

Said another way or more specifically, can you be Pentecostal and a feminist?

I believe both Linda’s work, through historical biography, and my work through a critical-theological transdisciplinary approach, both answer YES!

For those unfamiliar with the paradoxical impulses we’re talking about, let me read a paragraph from my work, which summarizes the scholarship on this, including the very foundational work some of these panelists (and our chair!) have done:

"The early rise and later decline of women in leadership reveals a tension within Pentecostalism: the capacity to encourage and to discourage egalitarian practices, or what Bernice Martin termed the Pentecostal gender paradox. Pentecostal scholars have alternatively articulated Martin’s argument as the competing impulses of liberation and limitation,[1] freedom and formalization,[2] affirmation and denial,[3] opportunity and constraint,[4] and exclusion and embrace[5] concerning women in leadership.[6] The conclusion among these authors is that these competing impulses lead to tremendous uncertainty, hesitancy, or ambiguity about the place of women in Pentecostal circles." (Pages 7–8)

So my work argues for a consistent and critical theological method and vision across historical, biblical, and practical Pentecostal disciplines, that I believe offers a (dare I say “final”) solution capable of resolving this Pentecostal gender paradox (a bold claim, I know, but you might as well go big!).

And that critical solution is what I call an eschatological authorizing hermeneutic.

But the conference theme/question here, which I’ve been asked to incorporate, is:

How might the academic task be considered worship? How might the academy inform worship?

So for my few minutes here I want to focus on how the way women are treated in the academy (and specifically theological education and classrooms) might impact worship practices. And I feel this is a very relevant focus for this setting as most are involved in teaching and higher education.

I want to ask the question: should (or can) a Pentecostal education be a feminist education?

Most of this comes from a section of Chapter 6 which is all about how an eschatological-egalitarian vision impacts our worship and praxis, such as denominational structures, the language we use in worship, the stories we tell in worship, the gendered embodiment of our sacramentality in worship, and more. And it also includes in the classroom, which is this section, called:

6.2 Theological Education: Forming an Eschatological Consciousness

This section's focus is on how to create an egalitarian educational experience congruent with a Pentecostal eschatology of gender so that future Pentecostal leaders are prepared to construct worship that participates in eschatological–egalitarian realities and lead in a way that reifies their eschatological convictions.

6.2.1 Eschatological Pedagogy: Incorporating Women’s Voices

An eschatological–egalitarian approach to Pentecostal education will equally incorporate female voices, interpretations, and stories into theological instruction and the building (and critiquing) of theory and practice. In other words, Pentecostal theological formation in general should be “feminist” in its most basic definition of considering women’s experiences for theological reflection. Keeping women and their thoughts, writings, and contributions at the margins of theological instruction is not consistent with the eschatological–egalitarian heart of Scripture or the Pentecostal movement. An Acts 2 understanding of the “last days” is that hearing all voices—particularly of both men and women—is integral to knowing and understanding God (Acts 2:17-18).

Despite its congruence with Pentecost-inspired thinking, embracing a feminist approach to Pentecostal theological pedagogy likely represents a major paradigm shift. But by ignoring feminist theology, Lisa Stephenson argues Pentecostals will continue to fuse “an ideology of Spirit empowerment with a hierarchical anthropology”; in other words, the gender paradox will continue to thrive in our worship practices. Feminist theology helps to expose the patriarchal tendencies of theology and ecclesiastical structures that silence women.

For example, systematic theology and its traditional order have been challenged by many feminist scholars as a male-centered epistemology. A change several feminist theologians have suggested or implemented is putting methodology and theological rationale at the end of a work, challenging its unquestioned status by overly systematic male theologians.

In her theological memoir, theologian Roberta Bondi (the first woman to attain tenured faculty status at Candler School of Theology, Emory University) reflects on her learning experience and how “theology was abstract, logical, propositional, and systematic, and so was its God.” She describes how she had to deconstruct her theological education, unlearning and relearning what Christian doctrines mean and do not mean to women in her time.

Many theological students like Bondi (whether male or female)—and let’s say Pentecostal theological students—have had a similar experience as the one Rosemary Radford Ruether describes:

Writings by women themselves or writings expressing alternative views to the dominant tradition have often been dropped out of the official tradition, and their remains have to be dug up through careful detective work. But the dominant male tradition about women is not hidden at all. It lies right on the surface of all the standard texts . . . and its message has been absorbed and taken-for-granted over the generations. It takes a new consciousness to go back and isolate this whole body of material as a problem rather than as normative tradition. . . . No professor ever taught me to recognize it as an “issue.”

For Pentecostals, I propose this “new consciousness” is an eschatological one, where the eschatological understanding of God’s plan for equality informs Pentecostal theological inquiry.

There are several ways Pentecostal teachers can develop and teach this consciousness. For starters, they can introduce themselves and their students to feminist authors and thought. Ruether laments that “most male students and faculty still do not read [feminist] literature as a necessary part of their education and scholarship.” The theological world is just starting to come to grips with a history dominated by male readings and interpretations. Pentecostal educators should carefully choose textbooks and reading assignments, being aware of how women’s voices might be left out. (I give a few examples here, including my own where . . .)

For teaching a basic Introduction to Theology course at a Pentecostal university, I chose a textbook that was within Christian orthodoxy but that also incorporated feminist ideas, criticisms, and language into almost every topical chapter.

Hermeneutics or book study courses might suggest commentaries written by women for all classes and incorporate their insights into the classroom. Foundational courses on the Bible could require The Women’s Bible Commentary as a textbook or for inclusion in students’ personal pastoral/theological libraries, as it represents “the first comprehensive attempt to gather some of the fruits of feminist biblical scholarship on each book of the Bible."

But, reading the right theological textbooks is only half the battle. Women bring their own perspectives, experiences, insights, and questions—sometimes quite different than men’s—to theological and biblical discussion in the classroom and other academic contexts.

However, studies have revealed many gender discrepancies in theology classrooms. Women in these classes are more silent and passive than males, and research [has] . . . determined that professors talk more to their male students and treat males differently (and it’s likely true of pastors or denominations leaders as well). Therefore, there needs to be open and honest discussions about these realities in Pentecostal educational circles . . .

An eschatological consciousness that values the biblical hope for equality will correct the gender-based power imbalance in theological texts as well as in the classroom, while also seeking to construct new egalitarian ways of writing, teaching, and learning theology.

Just one example of incorporating feminist thought is Pentecostal teachers can reassess how eschatology itself is taught as a theological discipline. Feminist theologians have often been antagonistic or at least dismissive toward traditional eschatology due to its male-centered, individualistic, and otherworldly focus. However, a more praxis-oriented Pentecostal eschatology aligns well with feminist thinking, and it can also learn from it.

Eschatological hope that incorporates the voices and perspectives of women is less likely to focus on the self and more likely show concern for the condition of all humanity. A female-oriented eschatology might focus more on how to make the world more livable for the children and generations to come, moving pedagogical approaches away from abstract and systematic ideas and toward how theology can improve the lives of the marginalized, including women.

I then give some examples in my book of common feminist redefining or rereading of eschatology, and conclude with this:

Teaching eschatology with the inclusion of female voices brings more perspectives to the table than the classic definitions of eschatology used in most Pentecostal institutions, definitions historically dominated by male-influenced worldviews. Furthermore, presenting alternative eschatologies can lead to more women sharing their experiences of how they think about eschatology, the afterlife, and how it impacts their Christian living.

So this is just one of the many ways I suggest we can begin to convincingly resolve the current gender paradox within Pentecostalism and bring feminist thought into Pentecostal pedagogy.

Transition to Linda's Presentation:

But Linda’s work on Bernice, which by the way is a delightful read (I’ll have a glowing review coming out in Pneuma), puts this paradox front and center in a lot of ways.

Despite Gerard being ordained for over forty years and having co-founded, with another woman, and pastored a vibrant church in Vancouver for over 20 years, she was still forced to defend herself as a woman leader.

Linda writes:

“it is understandable that as a woman in her sixties, with a lifetime of ministry experience to her credit, Gerard would feel weary and disrespected when she found it necessary to rise on the [general] conference floor [of the PAOC] to speak in favour of an initiative that could clear the way for more women to take up ordination credentials and do what she and countless other Pentecostal women had already been doing for decades” (169)

And Linda’s work is full of these illustrations of what she calls “messy contradictions” in Pentecostalism and in Gerard’s life (14) and the paradoxical relationship of her faith and feminism.

And so I’ll turn it over to Linda before we hear from our panelists.

* * * * *

Selected footnotes (from the book):

[1]

Estrelda Y. Alexander, Limited Liberty: The Legacy of Four Pentecostal Women Pioneers (Cleveland, OH: Pilgrim, 2008); Andrea Hollingsworth and Melissa D. Browning, “Your Daughters Shall Prophesy (As Long as They Submit): Pentecostalism and Gender in Global Perspective,” in A Liberating Spirit: Pentecostals and Social Action in North America, ed. Michael Wilkinson and Steven M. Studebaker (Eugene, OR: Pickwick, 2010),176–8.

[2] Charles H. Barfoot and Gerald T. Sheppard, “Prophetic vs. Priestly Religion: The Changing Role of Women Clergy in Classical Pentecostal Churches,” Review of Religious Research 22, no. 1 (September 1980): 2–17. This article obviously precedes Martin’s and has been equally influential. Its context is more the early Pentecostal movement; therefore, it will be discussed in Chapter 2. Similarly, Frederick L. Ware discusses “spiritual egalitarianism” versus “ecclesial pragmatism” in “Spiritual Egalitarianism, Ecclesial Pragmatism, and the Status of Women in Ordained Ministry,” in Alexander and Yong, Philip’s Daughters, 215. See also Powers, “Pentecostal Hermeneutics,” 314.

[3] Pamela Holmes, “The Spirit, Nature, and Canadian Pentecostal Women: A Conversation with Critical Theory,”in Alexander and Yong, Philip’s Daughters, 187.

[4] Qualls, Forgive Us, 153. See also the observation of Diedre Helen Crumbley concerning “Pentecostal paradoxes that liberate the body in worship while constraining its sexuality” in “Dressed as becometh Holiness: Gender, Race and the Body in a Storefront Sanctified Church,” in Spirit on the Move: Black Women and Pentecostalism in Africa and the Diaspora, ed. Judith Casselberry and Elizabeth A. Pritchard (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2019), 91.

[5] Cheryl Bridges Johns, “Spirited Vestments: Or, Why the Anointing Is Not Enough,”in Alexander and Yong, Philip’s Daughters, 170–1.

[6] It should be noted the starting premise for these Pentecostal scholars is the opposite of Martin. Whereas Martin sees Pentecostalism as a mostly patriarchal movement that sometimes surprisingly brings new freedoms for women, most Pentecostal scholars view Pentecostalism ideally as an egalitarian movement that often surprisingly restricts the ministry of women. Nevertheless, the important conclusion and consensus is that there are two competing impulses which create a paradox in Pentecostalism regarding gender and the role of women.

[7] These terms will be used interchangeably throughout my work to refer to the issue of women’s (in)equality in Pentecostalism.

RELATED POSTS:

"Excerpt from Chapter 6: Participating in the Eschaton"

Remember, you can read the entire Introduction to the book here.

Want to purchase or pre-order the paperback? Info and discounts HERE.

NEWSLETTER SIGNUP (blog post layout)

ABOUT JOSEPH

Pastor, Author, and sometimes pretends to be a scholar

Joseph (PhD, University of Birmingham) is the author of The Pentecostal Gender Paradox: Eschatology and the Search for Equality.

Since 2015, he and his wife have together pastored Oceanside Community Church on Vancouver Island, where they live with their four children.